Poaching in Regency England: Hunger, Risk, and the Price of Being Caught

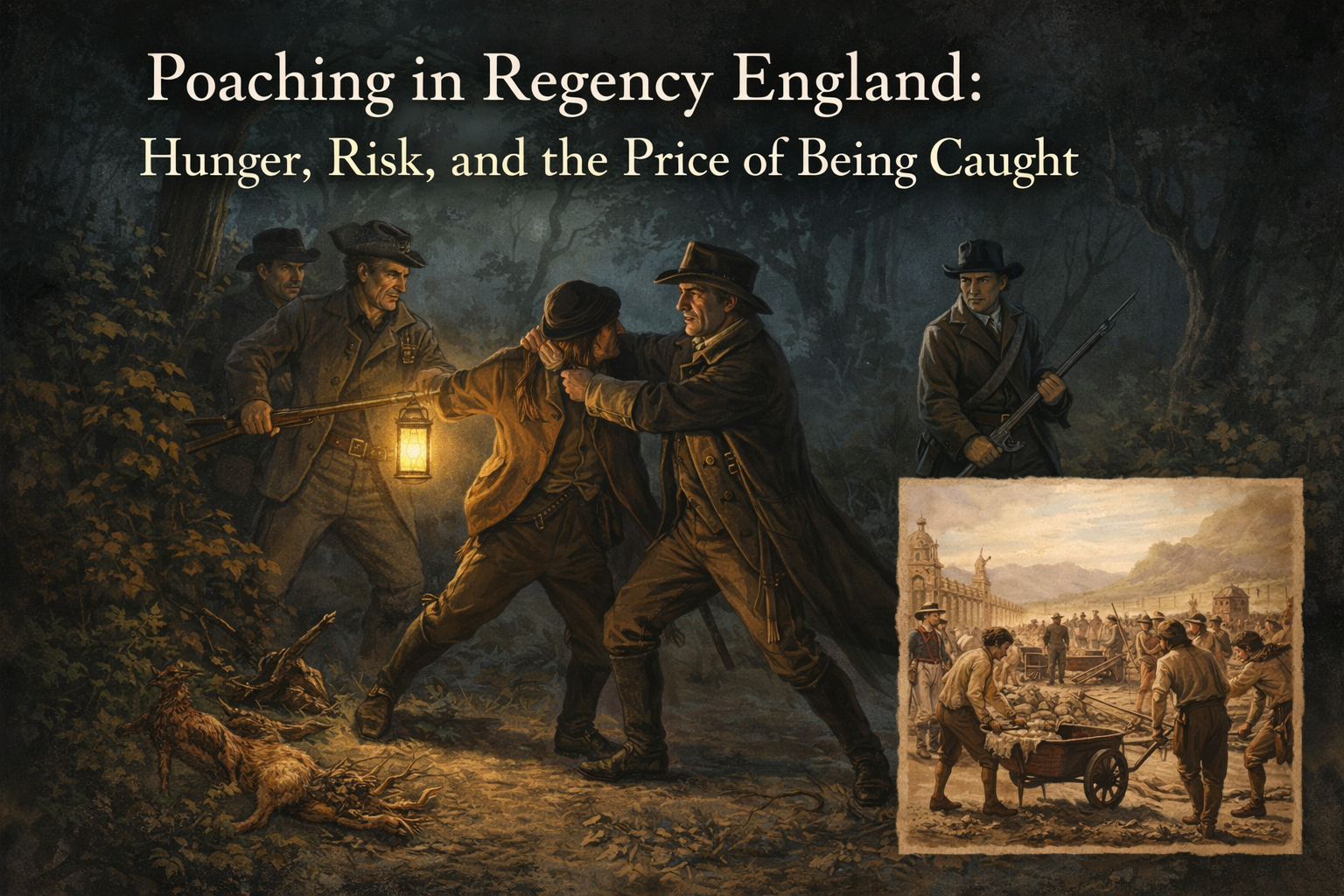

In Regency England, poaching was not a petty crime. It wasn’t a slap on the wrist or a stern lecture from a magistrate. It was a gamble—often taken out of desperation—and the stakes were brutally high.

Game laws existed to protect landowners, not empty stomachs. Deer, rabbits, pheasants—these animals belonged to the estate, not the people living beside it. Taking them without permission was theft, regardless of hunger or necessity. And the law had very little patience for explanations.

By 1816, the Game Act made the danger unmistakably clear. A poacher caught armed, in company, or under cover of darkness could be sentenced to death on the spot. No appeals. No second chances. Even lesser offenses—setting traps, trespassing to hunt, taking game without violence—often ended in transportation. Seven to fourteen years shipped halfway across the world to Van Diemen’s Land, a penal colony so harsh it was effectively a life sentence. Survival was uncertain. Return was rare.

Poaching terrified landowners and gamekeepers alike, not because it threatened sport, but because it threatened order. A poacher knew the land. Knew the woods. Knew how to move unseen. That made them dangerous in a way polite society preferred not to acknowledge.

The bottom line is that In Regency England, poaching wasn’t about rebellion or romance. It was about survival—and the law answered survival with exile or death.

That reality shapes the life of Juliet Finch in The Bird of Bedford Manor. When she traps and hunts on land that isn’t hers, she isn’t chasing adventure—she’s choosing between starvation and a noose. Every step she takes through the woods carries real consequence, and when she’s caught, the danger is immediate and unforgiving. Juliet’s story isn’t an exception to the rule. It’s proof of just how merciless those rules truly were.

Pick up your copy of this exciting tale at Amazon, Barnes and Noble, or a favorite bookseller near you.